What is Decision Intelligence? (Decision Modeling Intro)

I have a lot of fun technical topics I want to discuss related to Decision Intelligence (DI), and the process of creating standards, data formats, and tooling for DI as part of my work for OpenDI.

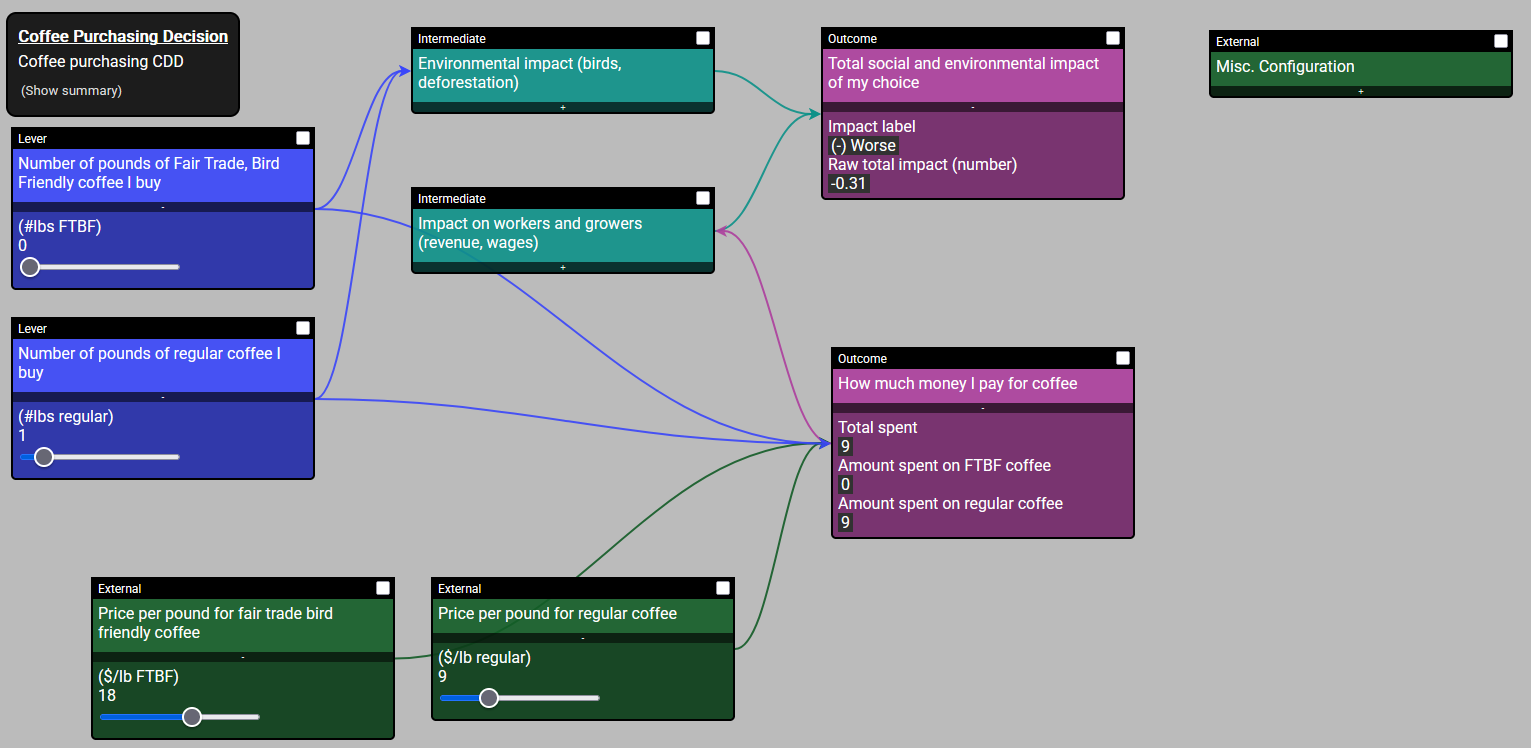

(I made this tool! You can try it here, in your browser.)

There is good introductory material out there for understanding DI, but it's generally not well suited as a lead-in for the topics I want to write about. So I'm laying my own groundwork!

We'll start by defining Decision Intelligence and some of its core concepts.

I'll note up front that most of the concepts in this post are based on the work of Dr. Lorien Pratt, who invented DI in the first place. The DI Handbook that she co-authored with Nadine Malcolm is the best resource around if you want a deeper dive into DI.

What is Decision Intelligence?

This term is chaotic right now. When you look it up, it's hard to find a consistent definition for it.

Sometimes you find jargon soup:

"Start with a data stock. Add a dash of machine learning, 1 teaspoon of AI from concentrate, 3-5 visualizations (shelled), and 3/4 cup of diced managerial theory.

Pressure cook on high for 25 minutes. Serves 3 LinkedIn posts."

Or you get vague generalizations:

"It's when you use AI to help make decisions!"

I think this definition from Gartner is decent:

"Decision intelligence (DI) is a practical discipline that advances decision making by explicitly understanding and engineering how decisions are made and how outcomes are evaluated, managed and improved via feedback."

This definition implies some follow-up questions that are actually specific and useful:

- How do you turn decision-making into an engineering process?

- How do you evaluate outcomes?

- What should those feedback processes look like?

One reason DI gets turned into jargon soup is because decision-making is hard. We've already created lots of disciplines that approach it in different ways. DI often acts as an integration framework that helps align these existing tools and disciplines around common principles. So a lot of the disciplines attached to those tasty bits of jargon are still involved, but you can't just hand a data scientist a Large Language Model and expect Decision Intelligence to materialize.

You need structure!

Modeling decisions

Most of this post will be about that first follow-up question:

How do you turn decision-making into an engineering process?

In short, you model decisions!

If you can deconstruct the concept of a decision, break it down into a vocabulary of common components and features, then you can use that vocabulary to describe any decision you want.

Why is this useful?

Once you have a common vocabulary, you can write stuff down.

You can capture decisions! You can draw them.

If every stakeholder involved can see a decision laid out visually, any one of them can point at it and say "actually, I think it should look like this instead".

Conversation is the classic medium for decision-making. But conversation is fuzzy! Everyone has their own perspective, and it can take a lot of careful discussion to tease apart discrepancies in each person's mental image of a situation. When you model the decision instead, you can collaborate to synthesize those individual mental images into a more concrete consensus. You can align around the mechanics of a decision.

When your model is digital, and your vocabulary is sophisticated enough, you can even do simulation!

Whether you're doing realtime decision simulation or you're just collaborating on some whiteboard doodles of decision diagrams, DI offers enough of a framework that engineering can take place. You can begin to conceptualize and discuss decisions as systems.

Causal Decision Models

Let's dig into the specific vocabulary for those systems!

DI represents decisions visually as special Directed Graphs, where elements in the directed graph are related to each other by cause and effect.

When an arrow points from Element A to Element B, you can say that Element A causes Element B.

Each element in a Decision Model fits into one of a few categories.

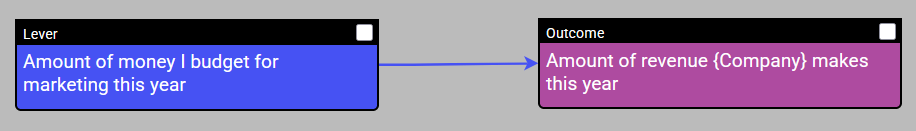

Levers and Outcomes

These elements frame the boundaries of a decision. When you're trying to draft a Decision Model, it often helps to brainstorm elements in these categories first.

Levers

Levers represent the actions available to the decision-maker.

They answer the question "What can I do in this situation?" by providing some possible options.

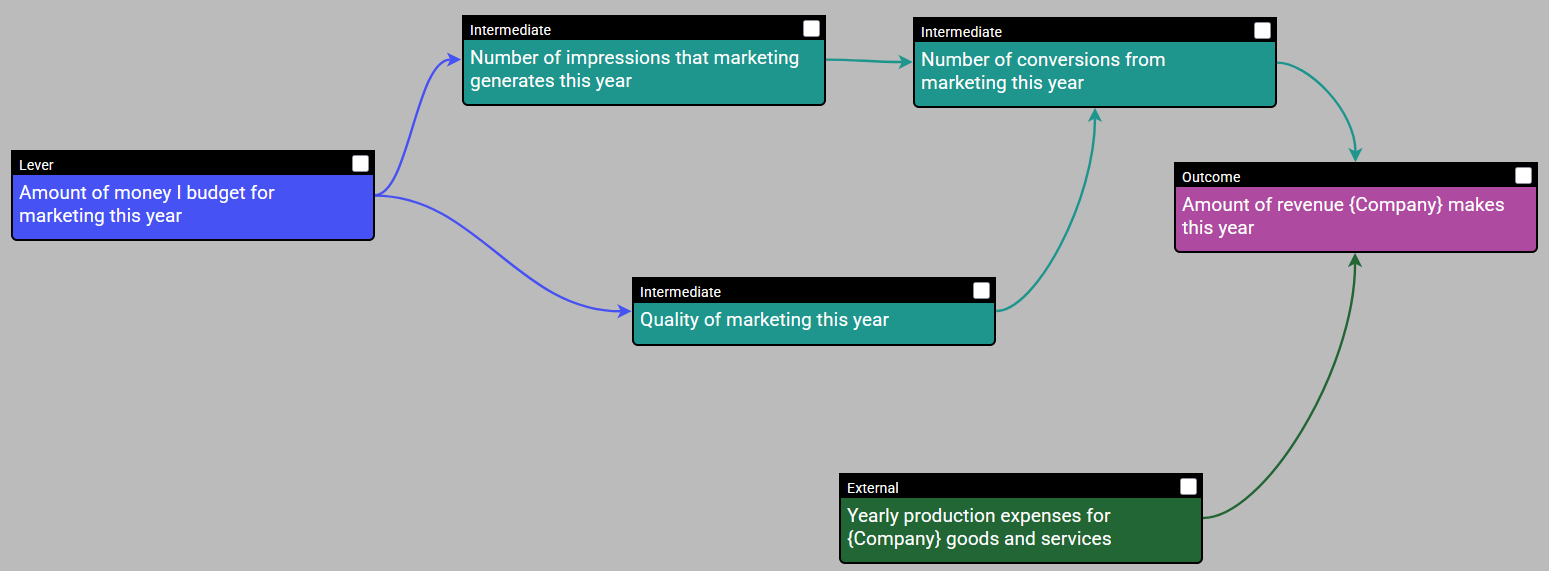

An example might be "Amount of money I budget for marketing this year".

Outcomes

Outcomes represent end results of a decision.

This is not necessarily the same as a Goal, since Outcomes generally don't judge the success or failure of the decision.

An example might be "Amount of revenue {Company} makes this year".

A Goal would place a constraint on this Outcome, like "{Company} makes ${amount} in revenue this year".

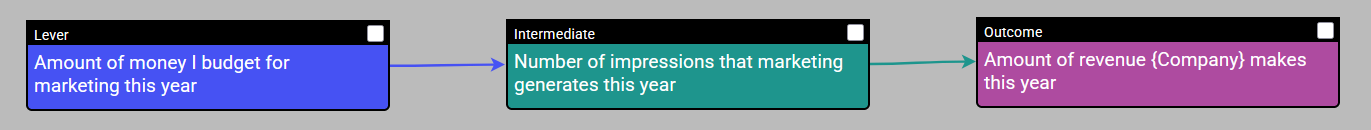

Intermediates

Intermediates fill in all of the causal relationships between Levers and Outcomes.

Sometimes Element A does not directly cause Element B.

An example might be "Number of impressions that marketing generates this year".

Intermediates are tricky. There are often many indirect links between any given Lever and any number of Outcomes. It's common to fill these in by iterating, working inward from Levers and Outcomes.

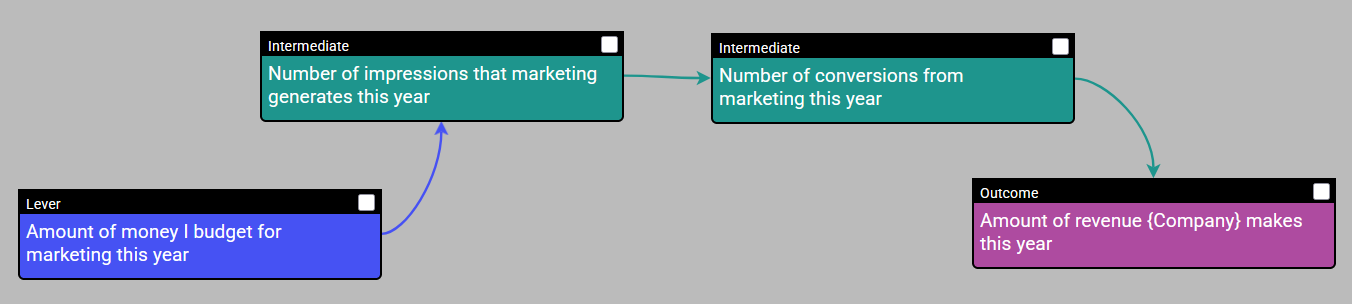

Iterating with "how" and "why"

To discover downstream Intermediates, ask "Why?". To discover upstream Intermediates, ask "How?".

Let's explore this approach!

Expand for examples:

In the above example, you might ask:

Q: Why are we considering changing the marketing budget for this year?

A: Because it will impact the number of impressions our marketing campaign generates this year.

And further,

Q: Why is the number of impressions this year important?

A: Because somewhere further downstream, impressions will impact our revenue this year.

From this exercise, you might conclude that it would make sense to add more intermediates to this model!

Q: Why is the number of impressions important?

A: Because some of those impressions convert into new customers, which impacts revenue.

Going the other direction, you might ask:

Q: Aside from changing the number of impressions, how else could we get more conversions out of our marketing budget?

A: We might improve the quality of our marketing.

We could go much further, but we'll leave the example here for now:

Externals

Externals are similar to Levers. They directly affect Intermediates or Outcomes.

Unlike Levers though, Externals are outside of the decision-maker's control for the current decision.

Externals answer the question "What else might impact this situation besides me?" by providing some possible options.

An example might be "Yearly production expenses for {Company} goods and services".

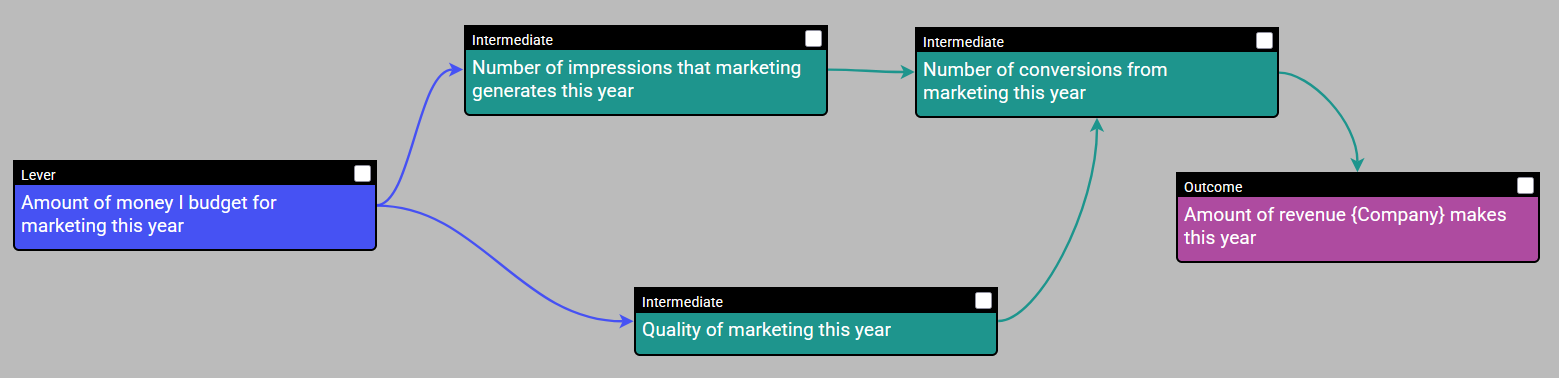

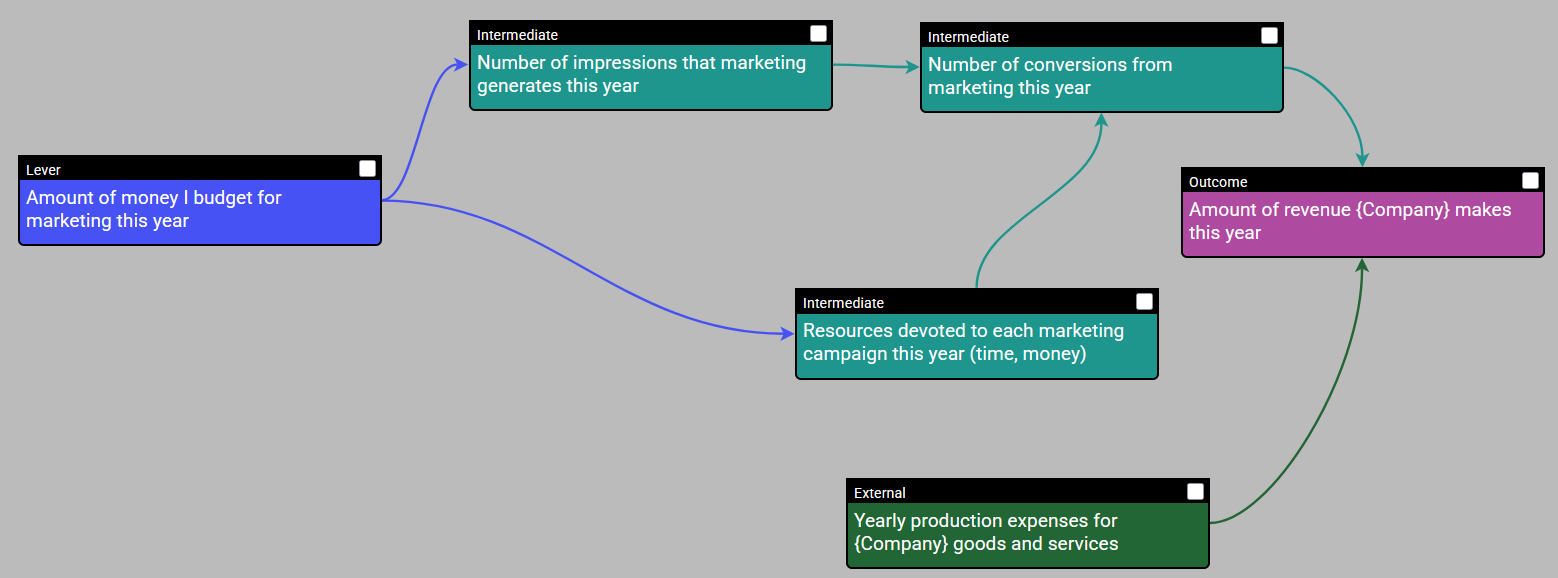

Keep it quantifiable

Decision elements are much more useful when they represent something quantifiable.

What are the units for each Lever, Intermediate, etc.?

Not only does quantifiability simplify simulation later on, but it also more clearly illustrates stakes and value.

When is this happening, and exactly how much will it help?

If you were bothered by the vagueness of our Quality of marketing element, this might be why!

Let's modify it slightly. How might we measure marketing quality? Maybe we could focus on the resources allocated to each individual marketing campaign.

This gives a better idea of what sorts of numbers we might associate with this element.

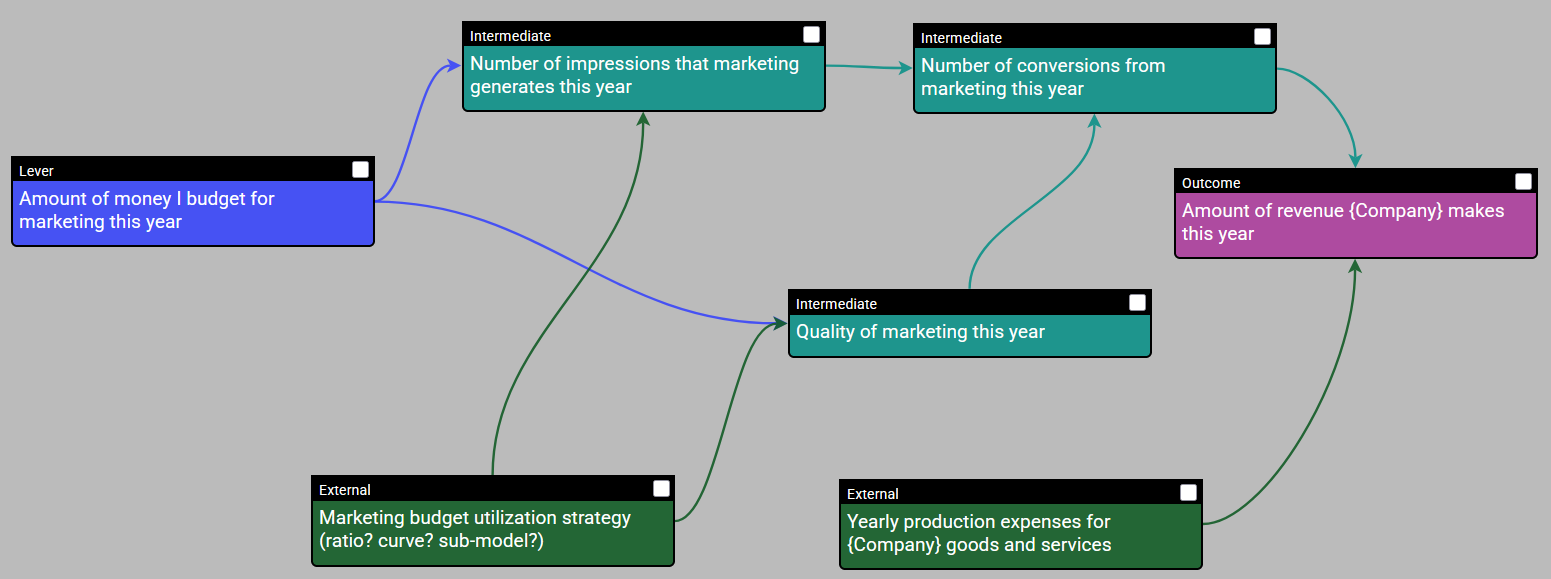

Decision Scope

Some of you might still be asking "How?" and "Why?" for the elements we have now. As you fill in gaps around these Intermediates, you might wonder how much of this budgeting decision depends on how the marketing team decides to utilize the budget you give them. There are lots of different things they can do with that money!

What you've uncovered is essentially another decision embedded in your original one. A good rule of thumb is that your model should be carefully scoped to consider only one decision whenever possible. The decision-maker needs to have agency over all of the relevant Levers for that one decision.

In this case, "marketing budget utilization strategy" might become an adjustable, flat ratio of some sort (e.g. quality vs. quantity), representing this utilization decision as an External. This way you can account for a range of possibilities without having to make that decision yourself.

You could easily make this more complex! You could set up your ratio as a curve across a range of possible budgets. You could build a resource allocation algorithm based on prior data.

If it's a big enough concern, you might decide to sit down with your marketing team and model this utilization decision with them, to give you a better idea of how to account for it in your own decision. If you come up with a good model, you might even embed it into a simulated version of your budget decision model, as a sub-model.

Engineering decisions

In this post, we've already taken our example model through a design iteration or two.

We've added more Intermediates to fill in the causal links between Levers and Outcomes. We've considered quantifiability and scope. We've even noted a specific area where it could be useful to integrate prior data and talk to other experts (our marketing team).

This is engineering!

We could continue to refine this with more elements. We could hook up scripts and input/output values and run simulations. We might even find a specific area or two where it makes sense to add our dash of machine learning or our AI-from-concentrate, to help model some of these causal links.

For now, we're already approaching a better understanding of this particular decision!

At least in theory. I don't work in marketing, so hopefully I haven't misinterpreted or misapplied any basic concepts.

If I have, please let me know!

Looking ahead

This post set out to provide a solid foundation for the answer to this question:

How do you turn decision-making into an engineering process?

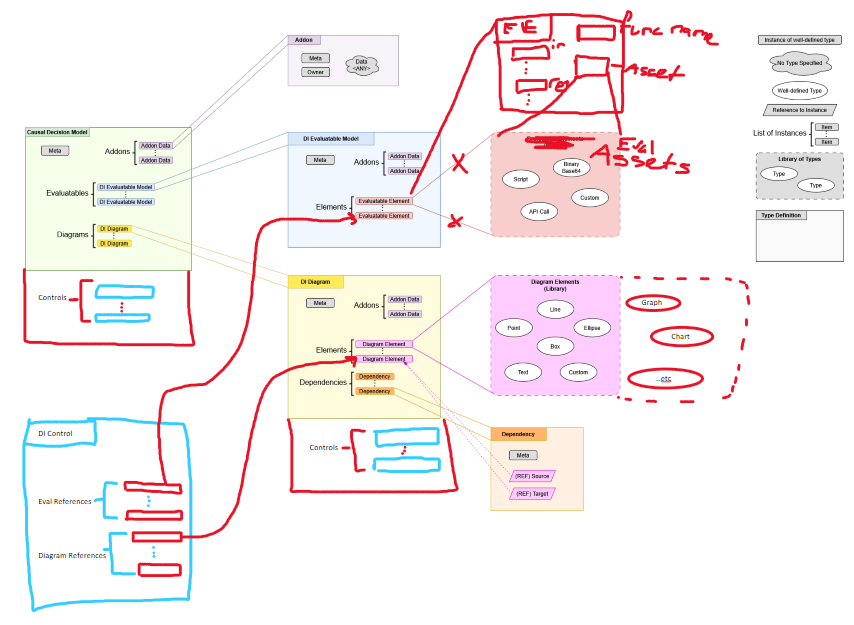

Moving forward, I have plans for a few topics about design decisions and challenges I've faced while building software solutions that help with the decision engineering process.

Over the past year I've built a browser-based engine for displaying and authoring interactive decision models, and designed data schemas for representing decisions, transmitting them, and using them in the engine. I have a lot to talk about!

I plan to talk about juicy WIP doodles like this (and some significantly more polished ones as well). Stay tuned!

You can subscribe to my RSS feed for post notifications.

Expand for info about edits

- Sep 17 2025: Couple minor line edits for tone

- See commit history